Apple first entered the laptop market with the release of the Macintosh Portable on September 20, 1989. The Portable was not a strong seller. Apple followed up the Portable with the PowerBook 100, PowerBook 140, and PowerBook 170, which turned out to be so successful that for a brief time Apple became the worldwide number one producer of laptop computers. But the success of latter depended heavily on the lessons Apple learned from the Portable.

The Portable project began around 1985. Apple head of product development, Jean-Louis Gassée, refused to bring the Portable to market before it was absolutely perfect. Apple had a serious problem with bringing products to market in the 1980s. The company was slow and ponderous, organized around functional lines rather than product lines like most other large computer manufacturers. Apple took at least two years to bring a new product to market. The Portable would be in development for 4 years.

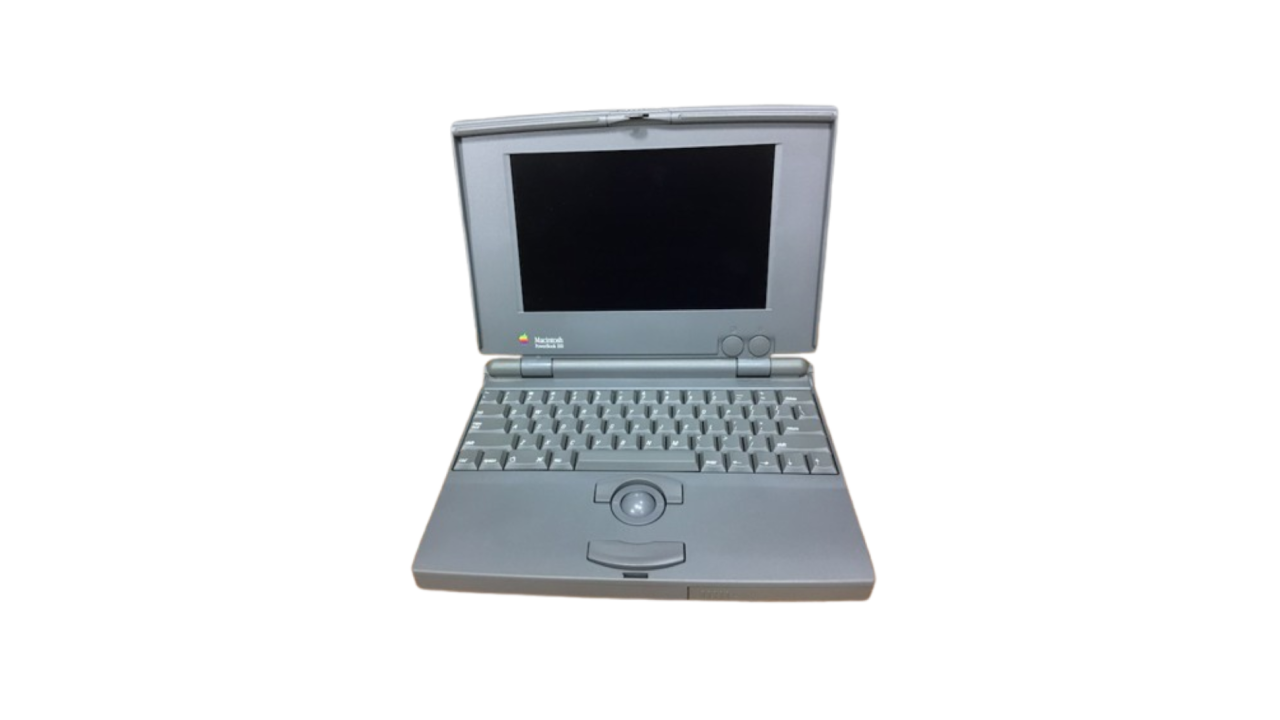

The Portable was meant to be a no-compromise design. It weighed an unbelievable 16 pounds. Basically, the Portable was a Mac SE in an easier to carry, slim case. The SE used an 8 MHz 68000 processor while the Portable had a faster 16 MHz 68000 processor. The most obvious difference between the Portable and the Mac SE was the Portable’s active matrix LCD monitor. The LCD monitor produced an extremely sharp image, but it had a few glaring drawbacks. Without direct overhead light, the screen was barely readable. Apple later corrected this problem on future Mac Portables by incorporating a backlit screen. The production of the large 640 x 400 pixel screen proved to be a challenge for Sharp, Apple’s LCD manufacturer. Sharp had difficulty manufacturing a defect-free screen. Apple’s solution to the problem was to lower their quality standards by accepting screens with 6 or fewer dead pixels. The Portable had a full size keyboard that could be configured with a trackball or keypad, although Apple recommended that this operation be performed by an Apple certified technician.

The Portable used the same ports as desktop Macs of the day. The Portable was more “luggable” than portable. Its heavy lead battery was part of its weight problem, but it did have perhaps the longest life of any portable on the market in 1989. The battery provided up to 12 hours on a single charge.

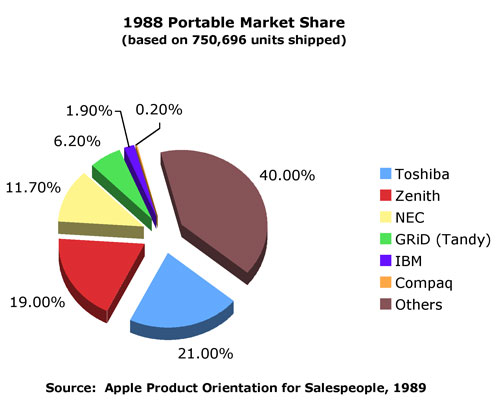

Apple was late to enter the portable market. As the chart illustrates below, one year before Apple introduced the Macintosh Portable, the portable market leaders were Toshiba (21%) and Zenith (19%). Apple estimated that worldwide unit shipments of portable computers would grow 38% from 1988 to 1989 and 66% from 1989 to 1990. They expected that by 1990, portable computers would account for 13% of all computers sold. IBM compatible manufactures had started early and each had invested significant resources into miniaturizing their hardware. During the same period, Apple concentrated on making ever larger desktop computers like the Macintosh II. Apple correctly identified the gap in its product offerings, but its conclusions about the market were divorced from reality.

Apple believed that what consumers wanted was a fully featured Macintosh with an enormous battery life. Portability was important, but Apple did not want to compromise the design in order to achieve greater portability. The company did not want to redesign the ports, or radically alter the internal components. The Portable was so large that it could not fit on airplane pull out trays and it was difficult to store under the seats. This no-compromise design would sell for around $6,500. The extreme price point would doom the Portable to the role of a minor player in the portable market.

Apple tried hard to give consumers the impression that the Portable was easy to transport, but it would soon be commonly referred to as “luggable”, because its 16 pounds of bulkyness meant it had to be lugged. A telling moment came at an Apple employee gathering at the Flint Center auditorium of De Anza College. An employee won a Portable at a company raffle. When the lady came to the stage to claim her price, she nearly dropped it because it was so heavy. There was quiet laughter in the audience, but the joke was on Apple, and it was no laughing matter.

The failure of the Portable was icing on the cake for Louis Gassée. He would not survive at Apple past 1990. A group within Apple headed by John Medica, Randy Battat, and Neil Selvin, began working on an unnamed project in 1990 to produce a true portable. Then-CEO John Sculley wanted the project to move quickly because the Macintosh Portable had failed to give Apple credibility in the portable market.

The group was unique for Apple at the time in that it was organized around the product. Marketing worked with product development. This allowed the group to proceed on the basis of feedback from marketing, who knew what customers wanted in a portable computer. The group realized that what consumers wanted was a light weight computer that could be used on an airplane with a medium duration battery life. Furthermore, business users on the go wanted a way to connect with their desktop computers at the office. Remote connectivity was solved with a remote version of Apple’s AppleTalk technology. AppleTalk had long been used to network Macs to printers and other Macs. Remote AppleTalk did the same thing except over hundreds and thousands of miles instead of just a few feet. Remote AppleTalk allowed users to check office email and share files with their office desktop Macintosh.

On October 21, 1991, Apple offered up three PowerBook models to replace the ill-fated Portable. Apple priced the PowerBook 100, 140, and 170, at $2,300, $3,000, and $4,300 respectively. The competitive pricing belies the extent to which the technology had advanced since the release of the Macintosh Portable. The Portable’s greatest contribution to this next generation family of portables was the active matrix LCD that had previously given Apple so much trouble. The high end PowerBook 170 was the only PowerBook to use the active matrix LCD, which made it highly regarded in the Macintosh community. Passive matrix LCDs like those in the PowerBook 100 and 140 and in most MS-DOS/Windows compatibles of the time produced inferior, shadowy images. However, the PowerBook 100’s and 140’s passive matrix LCD was an advanced liquid crystal display that rendered graphics and characters on the screen faster than other laptops using older technologies.

Having learned from the failure of the Portable, Apple miniaturized the components of its new PowerBooks. The PowerBooks used a smaller laptop internal hard drive and smaller laptop floppy disk drive. Instead of using all standard Macintosh ports, Apple used HDI-30 for the SCSI port and HDI-20 for the floppy port (only on the PowerBook 100). These were smaller versions of Apple’s standard ports, which made it necessary to use adapters to connect to most peripherals. The benefit of the smaller ports was a smaller chassis. The PowerBooks weighed in at 5.1 pounds for the 100, and 6.8 pounds for the 140 and 170. The PowerBook 140 and 170 used the 16 MHz 68030 processor while the PowerBook 100 used the older 16 MHz 68000 processor.

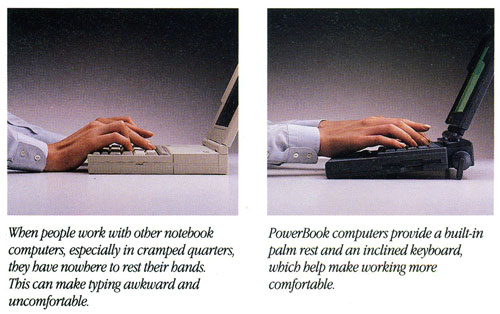

The PowerBooks were a revolution in portable design. Apple moved the keyboard to the back and positioned the trackball for ease of use. Contemporary portables of the time had the keyboard pushed forward and used clumsy detached mice. The PowerBooks did however have an ADB port if the user wanted to attach an Apple mouse. The PowerBooks’ keys were standard Macintosh keys but the keyboard design was compact, unlike the full size keyboard of the Macintosh Portable.

Apple believed that users would gravitate toward the 100 because of its price entry point. Apple geared up production of the entry level PowerBook, and cannibalized the production of the more expensive models. Apple used Sony to manufacture the 100, and built the 140 and 170 (which shared the same chassis) at Apple facilities.

Sculley did not give the PowerBooks high priority at Apple, having been burned by the expensive Portable disaster. Sculley stayed focused on Apple’s successful desktop offerings and only invested $1 million to market the new PowerBooks, compared to $25 million spent to kick off the Macintosh Classic, Apple’s popular $999 low-end desktop Macintosh. Apple hired basketball player Kareem Abdul-Jabbar to emphasize the compactness of the new PowerBooks. Kareem played himself, a man who was had just ended one career (his lucrative basketball career) and was flying coach (supposedly because he wasn’t making as much money anymore). Even with the lack of space, Kareem was still able to use his Apple PowerBook. The ad was a success and soon Apple was swamped with PowerBook orders.

Apple miscalculated the demand for the higher end PowerBooks. Instead of flocking to the low end PowerBook 100, such a pent up demand for an Apple laptop existed within the Apple community that buyers were willing to pay extra to get the high end PowerBook 170. Apple’s back order log grew larger and larger. Finally, Apple was able to iron out the shortage issue. PowerBook 100 sales would never meet with Apple’s expectations. The computer’s rather slow 68000 processor had little appeal in early 1992, even in a portable model. The PowerBook 100 did not have an internal floppy drive and its passive matrix monitor was clearly inferior to the PowerBook 170. The demand for PowerBooks was such that sales went up to $1 billion in the very first year of launch. Apple dethroned Toshiba as the leader in worldwide share of portable computer shipments.

Apple’s early misstep with the Portable set the stage for one of the greatest Apple success stories of all time, the PowerBook. Apple would continue to sell laptops under the PowerBook label until it introduced the MacBook in 2006. With PowerBook, Apple once again changed the playing field for the entire industry. Competitors would soon copy it just as they had come to copy many of Apple’s innovations.