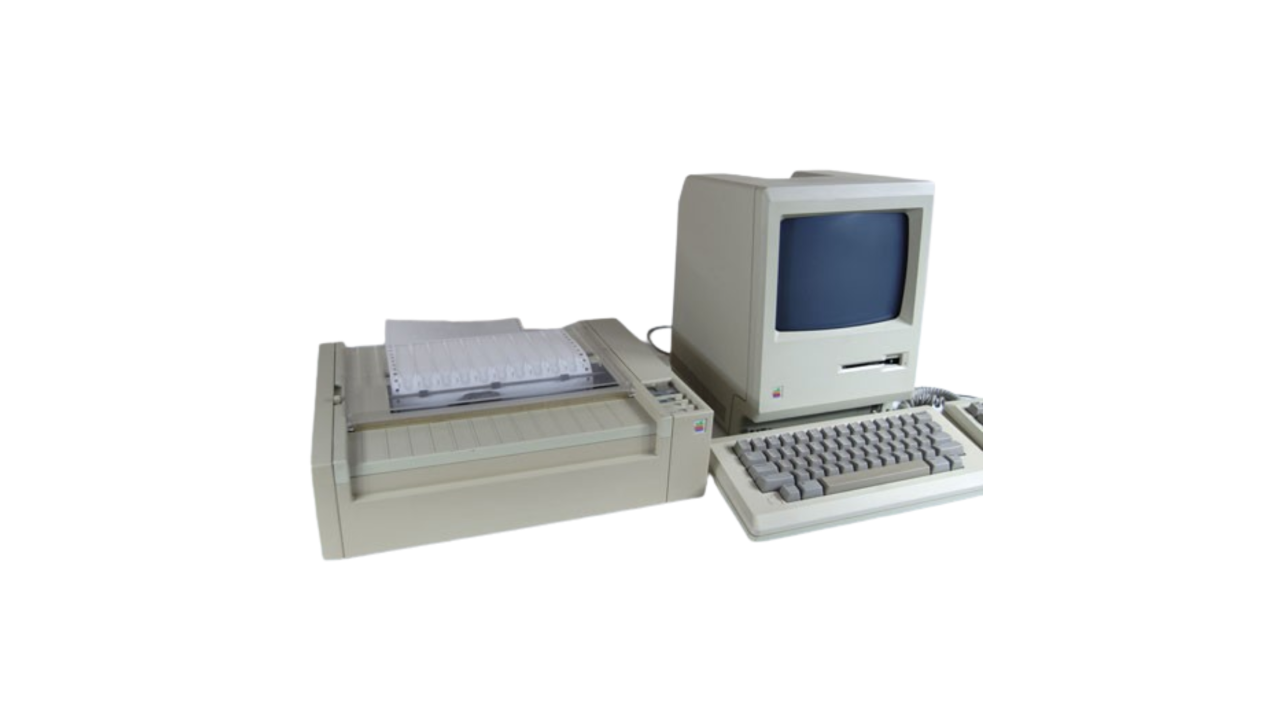

Apple introduced the ImageWriter dot matrix printer on June 1, 1984 as the standard printer for the Macintosh, introduced earlier that same year. The 9-pin ImageWriter, built by Tokyo Electronic, can print all Macintosh screen fonts and graphics, as well as screen dumps (replicas of the screen)[1]. The ImageWriter was originally conceived as a replacement for Apple’s earlier Apple II and III-compatible printer called the Apple Dot Matrix Printer (or Apple DMP for short), but quickly became synonymous with the WYSIWYG (what you see is what you get) motif offered by the new Macintosh computer system. The ImageWriter prints only in black and white. It can produce images and text up to a resolution of 144 dots per inch (DPI) up to a maximum speed of about 120 characters per second (CPS). The ImageWriter is compatible with all early Macintosh computers with a serial printer port, the Lisa and Lisa 2, all Apple II computers including the Apple II, Apple II Plus, Apple IIe, Apple IIc, Apple IIc Plus, and Apple IIgs, and the Apple III. Check specifications on Apple – Support for the configuration requirements of each platform.

Apple marketed the ImageWriter as an indispensable component of the Macintosh system. Upon its original introduction into the market in 1984, the Macintosh had no other compatible printers. The original Mac was a closed system with a standard set of ports. Third party printers would not become available for the Macintosh until the platform became established as a viable product in the eyes of consumers. Apple had no choice but to arrange for the manufacture of products like the ImageWriter to give the Macintosh platform a chance to establish itself as a market standard worthy of third party support. The ImageWriter offered plug and play simplicity for Macintosh users. All the Mac’s original software supported it and many accessories were designed to work with it.

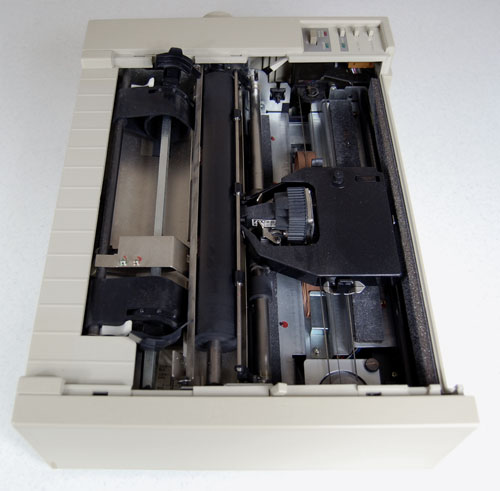

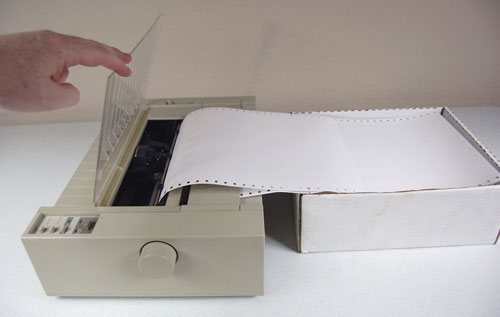

Dot matrix printers like the ImageWriter form characters out of little dots. The print head contains a set of tiny wires that dart in and out in a vertical array, pressing an inked ribbon against the paper as the head travels across it. The ImageWriter has 9 pins spaced at 1/72 of an inch apart[3]. More expensive dot matrix printers of the time had as many as 24 pins[1]. The ImageWriter is designed to use track paper, but feeding single sheets of regular paper one at a time is possible. The quality of the print is a function of how many dots per inch are used to form the image (text or graphics), not the force that is applied to strike the ribbon. Thus, images produced by the ImageWriter will appear faded as the ribbon wears out.

Draft Mode:

Draft mode is the fastest mode with the lowest print quality. Draft mode uses built-in characters and can only work for printing text, not graphics. Apple quotes a speed of 120 CPS for draft mode, but the true speed is about 50 CPS.

Standard Mode:

Standard mode prints at 72 DPI vertically and 80 DPI horizontally. Standard mode uses proportional spacing, so letter width can vary. For instance, a capital N would be wider than a capital I. Printing in standard mode produces a printed page almost exactly as it would appear on the Mac’s screen and the fonts used are sent from the Mac through the serial printer cable. The original Macintosh’s screen displays pixels at 75 DPI. The ImageWriter attempts to print a pixel-by-pixel correspondence with the screen, but because of the slight difference between standard mode resolution and the Mac’s screen resolution, vertical distortion results. Standard mode true speed is about 28 CPS.

High-Resolution Mode:

High-resolution mode prints at 144 DPI vertically by 160 DPI horizontally. High-resolution mode offers twice the resolution of standard mode. In high-resolution mode, the ImageWriter prints twice as many dots horizontally and makes two passes over the page for every line. The ImageWriter rolls the paper up the height of half a dot on the second pass, thus the dots overlap on the page by about 50 percent. Like standard mode, high-resolution mode also suffers from vertical distortion. High-resolution mode can be unsatisfactory for graphics with fine detail because the closely clustered dots can cause the image to look smudged. High-resolution true speed is about 11 CPS.

The ImageWriter has a built-in character set that includes the standard ASCII characters along with special ImageWriter characters. This character set is independent of the Macintosh, so it is not necessary to use Mac fonts to print. However, the Mac was designed to be a WYSIWYG computer system. The ImageWriter uses the Mac’s bitmapped fonts, in lieu of its own internal set of characters, to produce a document that approximates what the user sees on the screen. WYSIWYG output was very important to Apple in order to promote the concept of the graphical operating system and later, desktop publishing. Unfortunately, print quality was only just adequate. Apple would later release the very expensive LaserWriter printer to truly usher in the age of desktop publishing, but in 1984, the ImageWriter was a good start, not without its limitations.

To produce WYSIWYG, the Macintosh creates a bitmap internally and sends it to the printer. The bitmap is created in bands, and the printer pauses while the Mac’s software creates the next band. In high-resolution mode, a page contains 47 bands and 200 passes of the printhead. The original Macintosh only had a 72 DPI, 512 x 384 built-in monitor. Because of this restrictive resolution, you cannot see on the screen exactly what high-resolution will look like because the software adds additional dots to the printed page. The ImageWriter normally prints pictures elongated vertically about 11 percent compared to the Mac’s screen. This can be corrected by choosing the Tall Adjusted printing mode that is available with many programs. However, Tall Adjusted mode forces a compromise in printhead positioning that often results in an untidy image.

Another limitation of the ImageWriter is clumsy paper handling. Track paper, which is form feed by the ImageWriter on tractor pins, is pushed rather than pulled under the platen. Furthermore, the clear plastic paper guide gets in the way of single sheets and the first sheet of track paper. It is especially cumbersome with heavier-weight paper. This problem can result in a line of compressed print or banding at the top of the page. The problem can be solved by lifting the paper guide until the first page has printed. ImageWriter driver software attempts to solve this problem by “burbing” the paper at the top of each page, but this usually does not work very well.

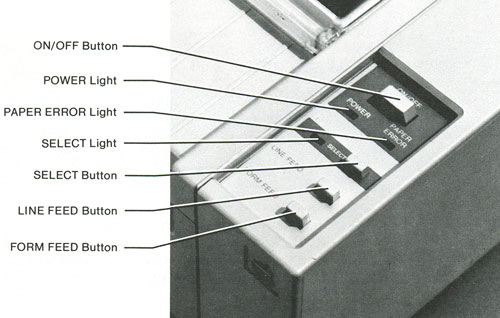

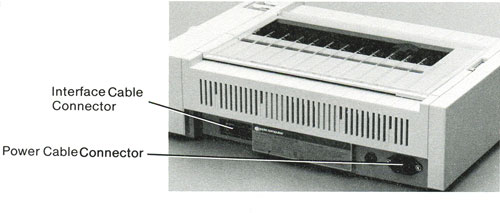

The first generation Macs, including the original Macintosh, Macintosh 512K, and Macintosh 512Ke all have a DB-9 serial printer port that can be used to connect the ImageWriter. Later compatible Macs have a mini-DIN 8 serial printer port and thus require a different printer cable. The ImageWriter has a RS232C 25-pin connector port located on the back of the printer. Pictured below is the ImageWriter to Macintosh cable that originally shipped with the printer. It is compatible with the DB-9 serial printer port of the first generation Macs. Connecting the ImageWriter to an early Mac is mostly plug and play with most of the printer’s functionality handled through the Mac’s software, but it is possible to modify the printer’s functionality in two ways: changing the DIP switches inside the printer case or formatting commands from the computer.

Each time the printer is turned on, the printer’s microprocessor is ready to follow a certain set of rules (called standard instructions) on how to print. Some of the instructions are stored within the microprocessor itself, while other instructions are determined by the DIP switch settings[5]. Apple provided extensive documentation on DIP switch settings and special control codes in the ImageWriter User’s Manual. However, it is rarely necessary to change the DIP switch settings or bother learning special control codes because the Mac (along with the factory-set DIP switch settings) handles all these things for the user. The same cannot be said for using the ImageWriter with the earlier Apple II computers, which were far less user-friendly and required a much higher degree of user expertise to configure with peripherals.

Apple discontinued the ImageWriter on December 1, 1985. It was replaced by the very popular and long-lived ImageWriter II. The ImageWriter II’s robust Apple industrial design solved many of the shortcomings of the ImageWriter. The ImageWriter, on the other hand, was primarily a re-branded third party printer optimized for and released in conjunction with the original Macintosh. The ImageWriter II has better paper handling, can print in color, is faster, and has superior connectivity options (AppleTalk). However, the same might be said of the original Macintosh in comparison to its later iterations. The ImageWriter was the best tool for the job in 1984 and it gave the original Macintosh enough WYSIWYG magic to make the world stand up and take notice of this revolutionary computer.