Apple has throughout much of its history resisted licensing its technology. This resistance has more than anything else fostered the creation of a separate and dominant industry standard, Microsoft Windows. Many insiders at Apple favored the concept of licensing in the early 1980s, but the company’s leadership as a whole, did not want to lose control of the Macintosh’s development path. Apple has always been a “religious” company. Its collective corporate culture has always believed itself to be the final authority of what constitutes the Macintosh experience. Apple resisted licensing the Macintosh architecture early on when it would have made a difference in the development and direction of the young computer industry. The company half-heartedly instituted a licensing program in the middle 1990s when it served only to cannibalize Apple’s operating revenues.

Many loyal Macintosh fans think Bill Gates is a hack who stole many of his concepts for Windows from Apple. This may be a bit of a stretch. After all, wasn’t it Steve Jobs who once said to his Macintosh development team, “Good artists copy; great artists steal.” And didn’t the Macintosh team fly the famous pirate flag, painted by Susan Kare? Bill Gates vehemently denied that he stole anything from Apple. The whole idea of GUIs had originated not with Apple, he pointed out, but with Xerox, “The father of the Mac is Xerox. The father of Windows is Xerox.” Charles Simonyi, Microsoft’s in-house GUI maestro, compared the similarities between Windows and the Macintosh to those found in different automobile models. “When you decide to build an automobile, you’re not going to change the steering wheel,” Simonyi says. “They all have common ancestry.”

In the early days, it wasn’t just Steve Jobs and Bill Gates thinking GUI, it was practically the whole industry. Digital research was working on GUI-based software called GEM. And another company called VisiCorp, which was famous for its successful VisiCalc spreadsheet program, demonstrated VisiOn at the fall 1982 Comdex show in Los Vegas. Bill Gates was so impressed by the demonstration that he had Charles Simonyi fly down to see the technology first hand. Until he saw the VisiOn in action, Gates had been preoccupied with building software to run on top of MS-DOS and the proliferation of smaller computer platforms on the market. Although VisiOn failed to reach widespread acceptance as an industry standard operating system, Gates correctly concluded that operating systems similar to VisiOn represented the future of the industry. Upon their return from the 1982 Comdex, Gates and Simonyi set to work on a graphically based operating system called “Interface Manager”, which would later be named “Windows” when the first version finally shipped in November 1985.

Bill Gates was no hack nor was he a fool. He would become the richest man in the world, and there was a reason for that. His company, Microsoft, was one of the most aggressive players in the young computer industry. He had his hands into everything on every platform that was marginally successful from the late 1970s onward. Pick up any old copy of Byte magazine or Macworld and you will see Microsoft advertisements for everything under the sun from Atari Microsoft BASIC to IBM Multiplan to Microsoft Word for the Macintosh. Microsoft was aggressive at marketing business applications, development environments, and operating systems. The Microsoft empire would rise to world dominance on the back of its IBM operating system called MS-DOS (Microsoft Disk Operating System). MS-DOS was the empire’s foundation and its programming languages and software applications helped Microsoft hedge its bets across all other competing platforms. MS-DOS would become the industry standard that everyone in the world of IBM-compatibles had to use[4] and the IBM architecture would dethrone Apple as the dominant architecture in the PC industry. But before IBM cemented its position as the industry dominate architecture, Gates worried about the threat of the Macintosh and its incredible graphical operating system.

Gates began his relationship with Apple in the late 1970s. Microsoft licensed Applesoft BASIC to Apple for use in the Apple II, which replaced Woz’s Integer BASIC. It would reside in Apple II ROMs throughout the production run of the Apple II family of computers. Furthermore, Microsoft developed a slew of plug-in cards and produced many development languages and “killer” applications for the Apple II. Microsoft’s support of the Apple II helped to establish it as an early standard architecture and many other companies would follow suit. So it should be no surprise that when Apple began developing the Macintosh, Steve Jobs turned to Gates to develop and market applications and development languages for the platform. Microsoft was a third party developer of the first order for the Macintosh platform. At times, Microsoft had as many people working on creating new Macintosh software as Apple had developing the Macintosh. Microsoft was one of the few companies with access to early pre-production Macs.

The Macintosh would make MS-DOS seem ten years out of date and Microsoft, working directly with Steve Jobs, gained early knowledge of this incredible graphical operating system. Microsoft threw considerable resources into developing for the Mac and Gates became worried in 1985 when Macintosh sales did not meet with expections. Concern for his own investment in the success of the Macintosh platform prompted Gates to became one of the strongest supporters of licensing the Macintosh technology. On January 25, 1985, Gates sent a detailed memo to Apple CEO John Sculley and Apple products developer Jean-Louis Gassée, begging them to consider licensing macOS to outsiders.

Having received no reply from Sculley or Gassée, Gates wrote a second letter on July 29, naming three other companies that would be receptive to licensing, and added, “I want to help in any way I can with the licensing. Please give me a call.” Gates’ overtures fell on deaf ears. Sculley didn’t understand the specifics of how to go about licensing and Gassée refused to relinquish the Mac’s advanced technologies to copycats. Other companies would go on to request Apple license its technology, among them AT&T; and Sony. Over time, vendors began to incorporate Macintosh-like innovations in their products. This began to slowly erode Apple’s clear technological advantage.

Apple’s Macintosh technology was unique in that a significant portion of macOS resided in the machine’s ROM chip. Due to the constraints of the hardware of the day, most notably memory and disk capacity, Apple hard-coded significant amounts of the operating system in what it called “the Macintosh toolbox,” which resided in ROM and was always available to be called by the portion of the operating system residing in the Mac’s RAM, which was loaded upon booting the system disk. Indeed, many at Apple argued that the thing that made the Macintosh different from all other computer systems had nothing to do with the hardware, but everything to do with what was in the ROM.

“Now that your selling Macintosh, you’re a software company, not a hardware company, because the thing that makes the Mac different from all other computers is nothing in the hardware, but it’s in that ROM. What your selling is services, communication services between human beings and what computers can do for them. When you’re in the software business, you have to run on every platform, so you must put the macoperating system on the PC and put it on Sun workstations and put it on everything else.”

Alan Kay, a Xerox PARC alum and former Apple Fellow

Apple never allowed companies access to its ROM in the 1980s. In fact, Apple would go further to secure the impression that it was a niche player by increasing the price of all Macs across the board in the late 1980s, following a premium pricing strategy. For Apple’s part, it was making money hand over fist, so the desire to license did not have pressing momentum for the company. Furthermore, Apple would attempt to sue Microsoft for copying the “look and feel” of macOS. The suit ended in a decision against Apple and amounted to a green light for Microsoft to continue to close the technological gap between Windows and macOS. And the technological gap was indeed immense.

“The computer was never the problem. The company’s strategy was. Apple saw itself as a hardware company. In order to protect our hardware profits, we didn’t license our operating system. We had the most beautiful operating system, but to get it you had to buy our hardware at twice the price. That was a mistake. What we should have done was calculate an appropriate price to license the operating system. We were also naive to think that the best technology would prevail. It often doesn’t.”

Steve Wozniak, Apple cofounder

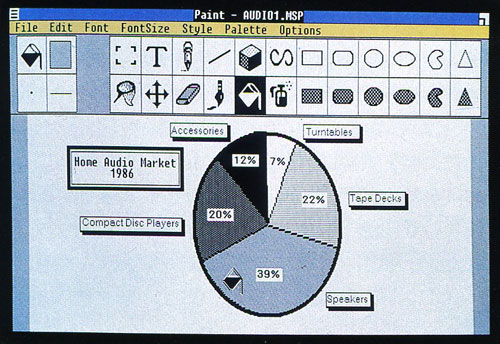

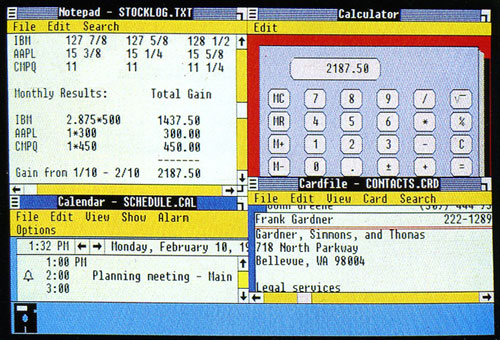

Below is a scanned article for the original version of Windows appearing in Byte magazine, April 1986. At this point in time, Windows was more of a disk manager than a graphical operating system. It was a graphical operating environment that ran on top of MS-DOS. The point of Windows is easy to see. It simplified that act of using a text-line computer. However, unlike the Macintosh, Windows allowed users to leave the GUI and run DOS-based programs. The Macintosh forced developers to design programs that took full advantage of the Macintosh GUI. Programs that deviated from Macintosh human interface guidelines would not make it on the Macintosh platform because users expected all Macintosh applications to have the same look and feel.

Microsoft’s not so impressive Windows GUI circa 1986:

Early Windows-compatible programs did not abide by any uniform set of human interface standards. The Windows GUI was not designed to be transcribed over all applications running on an MS-DOS machine. It was an attempt to simplify the maintenance of the computer and was optimized to take advantage of the IBM architecture’s limited ability to display graphics. Windows was not designed around a custom ROM chip like the Macintosh, and given the limited hardware of the day, it is not surprising that early versions of Windows looked primitive compared to the tailored mix of hardware and software available only on the Macintosh platform. Microsoft understood the limitations of Windows at the time. The above advertisement for Windows states that “One of the great beauties of Windows is that in the here and now you enjoy the benefits of computing’s future path – graphically oriented software. Without giving up any of the applications you’re happy with today.” What Bill Gates really understood was that if you wanted to experience a true graphical operating system of the future today (in 1986) you would have to buy a Mac.

“That’s not what a Mac does. I want macon the PC.”

Bill Gates arguing in favor of overlapping, not tiled, windows for Microsoft Windows.

The Macintosh community would soon find it hard to resist the irresistible momentum of the IBM architecture that benefited from an industry out-spending Apple on R&D; by a factor of over a hundred to one. The advantage of the Macintosh ROM would soon erode as the decade of the 80s ended and computer hardware was finally up to the task of providing a Macintosh-like interface running on Window-compatible computers without the need for a specialized ROM. When Windows 95 hit the scene in the middle 1990s, Microsoft had finally caught up with the Macintosh. It had an acceptable, true graphical operating system that was comparable to macOS. Apple’s future was in doubt as its market share drastically shrunk and this time around, Apple couldn’t simply raise the price of its computers to make up the difference.

At the shareholder meeting on January 26, 1994, Apple announced that it would license its upcoming Power Macs by the end of the year. Apple had trouble signing up even one licensee. Potential cloners questioned Apple’s commitment to long-term licensing. After a number of concessions and much hand wringing, licensees finally came onboard and began selling Mac clones in 1996. Cloners included Umax, Motorola, and Power Computing.

When Steve Jobs returned to Apple in 1997, many of the cloners began to worry about their future. During a fireside chat at Apple’s Worldwide Developer’s Conference (WWDC) on May 16, 1997, Jobs asserted his belief that clone vendors should pay more for the privilege of making Macs. Instead of a flat fee of $50 per unit, the price should be based on the volume and price of computers sold. He referred to cloners as “leeches”. It was clear that Jobs was no fan of licensing.

Apple was at a strategic crossroads. Having missed the licensing bonanza of the 1980s and only half-heartedly licensing macOS to aggressive cloners in the mid 1990s, Apple had a poor track record with creating an industry standard. Purists sneered at the concept of cloning. Who could really make a Mac but Apple? Unfortunately, economic reality pointed to the fact that the cloners where able to make Macs cheaper using common industry components and they were very aggressive at marketing their creations as the sensible Macintosh option. If you doubt the powerful influence Mac cloners had on the Macintosh community at that time, take a look at any mid-1990s edition of Macworld or MacUser. The proliferation of clone advertisements and articles discussing the price/performance of cloned Macs gives the impression that the cloners were the dominant force in the Mac world and that Apple was a minor player. Apple would have to choose. Does it want to be a software company like Microsoft or does it want to be something else; does it want to be Apple?

“When the Mac came out in 1984, we wrote to Sculley, and we told him who to go to at HP and who to go to at AT&T; to license the machine because we’d really bet our future on the Mac. We stopped doing DOS application development and did all our work in the graphical operating environment, so we were very worried in 1985 when Mac sales slowed down actually from the first year and we were trying to make all these suggestions. It’s probably too late to make a licensing program work.”

Bill Gates, in a speech on January 30, 1996

Apple was in a period of transition when Jobs assumed the role of strategic advisor on July 9, 1997 after the surprise resignation of then CEO Gil Amelio, who was a strong supporter of Mac licensing. The cloners had grabbed a significant portion of the Mac market share. Power Computing alone held 10% of the Macintosh market generating $11 million in profit on sales of $246 million in 1996, and its revenues reached $84 million in the first quarter of 1997. Apple took a close look at the opportunity cost of cannibalizing sales of Apple Macintosh computers for a license royalty for every Mac clone sold by the cloners.

Steve Jobs pulled the plug on the cloners late in 1997 by not extending their licenses to cover OS 8, Apple’s newest version of macOS. On September 2, 2007, Apple announced that it would acquire Power Computing’s customer database, its license to distribute macOS, and certain key employees for $100 million in Apple stock and roughly $10 million to cover debts and closing costs. As part of the deal, Power Computing agreed not to sue Apple for breach of contract. “Power Computing has pioneered direct marketing and sales in the Macintosh market, successfully building a $400 million business,” said Jobs. “We look forward to learning from their experience, and welcoming their customers back into the Apple family.”

In a memo to Apple employees explaining the acquisition, Jobs wrote, “The primary reason is that the license fee Apple receives from the licensee does not begin to cover their share of expenses to engineer and market the macOS platform. This means, in essence, Apple is giving a several hundred dollar subsidy with each licensed copy of the macOS. Our board is convinced that if Apple continues this practice the company will never return to profitability, no matter how well Apple performs, and the entire Macintosh ‘ecosystem’ will continue to decline, eventually killing both Apple and the clone manufacturers. This scenario has no winners.”

Steve Jobs has always been a hardware man. His philosophy was incompatible with the concept of licensing and perhaps this time around, he was right. There was no longer a compelling reason for Apple to license its technology. The underlying economics of the industry had changed. Apple’s reluctance to license in the 1980s fostered the creation of the Windows standard, but in the late 1990s, it was highly doubtful that any Apple licensing program could create a new dominant industry standard. Modern computers have transformed the way software is designed and implemented. The hardware has caught up the aspirations of the software. Macs have become cross-platform compatible with the ability to boot Windows or run Windows applications using visualization software like Parallels. Parallels Desktop for Mac has become the leading virtualization solution for the Mac, enabling Apple users to run Windows in conjunction with macOS X without rebooting. Under Steve Jobs’ leadership, Apple has been able to maintain control of the architecture while at the same time negating the need to license maOS.

Apple’s long struggle with licensing was really just a sideshow for Mac purists. Even though we would have been favorable to the creation of an industry dominant Mac standard beginning in the 1980s, it would have fundamentally changed the character of the company. Apple’s greatest strength has always been its greatest weakness: its urge to protect its fabulous proprietary technology. With the advent of visualization technology, Apple can jealously protect its superior operating system while maintaining its compatibility with everything not of Apple. Macs can run any old Windows app, but Windows-compatibles will always have trouble running macOS. It is the best of both worlds. Apple can push for innovation in the market because it controls all aspects of the Macintosh experience with its incredible propriety operating system and sublime Macintosh hardware.